“Come, let us slay the spirit of gravity! I learned to walk; since then have I let myself run. I learned to fly; since then I do not need pushing in order to move from a spot. Now am I light, now do I fly; now do I see myself under myself. Now there danceth a God in me. - Thus spoke Zarathustra.”

Friedrich Nietzchei

“I have stretched ropes from steeple to steeple; Garlands from window to window; Golden chains from star to star ... And I dance.”

Arthur Rimbaudii

It was the nineteen-century French Symbolist poet Stéphane Mallarmé who was the first to define dance as poetry of the body, and as a system of signs. In his theory of the aesthetico-metaphysical function of dance, he described dance as a “rite,” as the “expression of the Idea,” and as “the superlative theatrical form of poetry.”iii Among the performing arts, he deemed dance “…alone capable, through its summary writing, of translating the fleeting, and the sudden, even the Idea.” iv He thus allied and underscored two aspects of dance, which were not ordinarily simultaneously emphasized - its ritual character and its character as a writing, a system of theatrical signsv. For him, it was specifically the famed Moulin Rouge performer Loie Fuller who was the embodiment of an innovative dance poetics in action.

Mallarmé described her dancing as a kind of (unwritten) poetic text, and recommended that the spectator make the effort to read it: “The only imaginative exercise consists in…patiently and passively asking oneself before each step, each attitude - so strange those pointings, tappings, lunges, and bounds - What can this signify?”vi For Mallarmé the dancer’s steps are “emblematic” not mimeticvii; which is to say, that each step or movement represents an “essence” of dance. As such, the writing of dance can be compared to hieroglyphs, “not because its symbols are iconic,” as Mary Lewis Shaw explains, “but rather because this pictorial writing (like that of the musical score) has a mysterious and sacred quality and is difficult to decipher”viii.

It is Mallarmé’s concept of dance as a system of codes that is so successfully explored in Lena Liv’s most recent body of work, Dancing Makes Me Joyful - a collaborative project with dancer-choreographer, Lindy Nsingo, which took place at the sixteenth-century Villa di Corliano in Pisa in 2014. The series consists of three light-constructions, a large pastel drawing, and video documentation of Nsingo’s dance - each of which is an exquisite testament to the moments experienced together at the Villa. This complex body of work touches upon notions of migration, dancer-as-metaphor, and PreSocratic concepts of a universal “essence”. Central to the series is the initial meeting site, the extravagant villa, where Liv documented Nsingo’s dance performances.

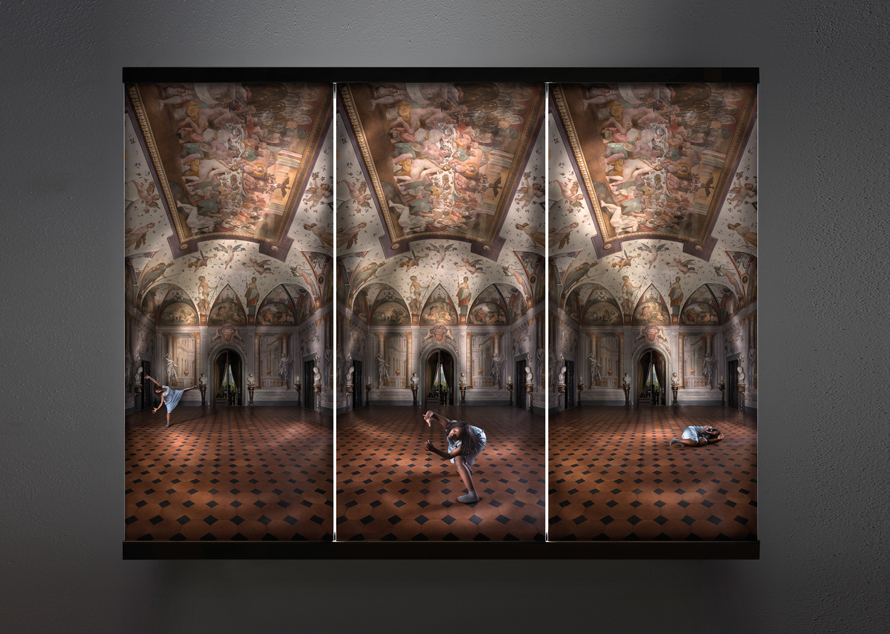

Located on the west slopes of Mount Pisano, surrounded by woods and olive groves, and a rococo-style park, the Villa di Corliano is considered one of the most beautiful mansions in Tuscany, replete with splendid interiors that are decorated throughout with beautifully executed frescoes depicting scenes from Ovid’s Metamorphosis, which were mainly produced by Andrea Boscoli, a well-known Florentine painter, in the 1590s (Fig. 1)ix.

During its heyday from the sixteenth to the nineteenth centuries, the villa was a trendy place to visit, attracting members of high society - including visits from the King and Queen of England, the Cardinal of York, General Murat, Louis Bonaparte, the romantic poets Byron and Shelley - who would inevitably have feasted/dined in the Central Hall, below a magnificent fresco depicting a mythological gods’ banquet, surrounded by images of flying putti, depictions of the Four Seasons, and portrait busts of great philosophers and goddesses, like Seneca, Plato and Minerva. It would have been a glorious environment - lush, sophisticated, ostentatious, and rich. (Today, the Villa serves as a tourist site, and, remarkably, is still owned by the noble descendants of the Della Seta family who purchased it in 1536.)

Walking into the villa in 2014, Nsingo was astounded. Born in Zambia in 1987, raised in Belgium and South Africa, and currently living in London, she had never - until that moment - seen such a luxurious building.

As she explains:

“I had never seen a palazzo before. It was my first time in Italy and I was very overwhelmed and taken aback by all the history, the buildings, and the art. I was in awe of the Villa di Corliano. It felt as if time had stood still there. And I could just imagine the fancy balls and the rich people the central hall had entertained. The size and scale of the frescos was impressive too! And I immediately wondered how I was going to respond choreographically to something I had never seen experienced before”x.

In preparation for the collaborative project, the Russian-born, Pietrasanta-based Liv had chosen the site quite specifically, knowing that it was a symbol of her experience of living in Italy, but not necessarily Lindy’s. Liv was interested in their shared migration stories, as global nomads who had experienced multiple cultures. As the two discussed the many places they had each lived (Liv has lived in Russia, Israel and Italy), Nsingo says that she began to think specifically of her African history, and the ways in which her family’s history has been passed down through stories. Moreover, as Nsingo explains, “The piece/dance was informed by ideas of migration and of responding to the foreign space.”

For the choreographed piece that resulted, titled mymothersshoes (2014), Nsingo sought to capture the “disjuncture” she felt within the space. The dance commences with Nsingo miming a traditional African tribal dance, in slow motion, to the recorded sound of her mother’s voice, who speaks in her native tongue, Bemba (a Zambian dialect). She is discussing the culture shock of moving from Zambia to Belgium, where she felt unwelcome and isolated. “In Belgium, my mother felt very sad and lonely,” Nsingo explains. As her mother speaks, Nsingo’s tribal mime continues, and quickens - both arms raised in unison as her feet stomp lightly. As her mother’s voice fades, music commences. It is Cliff Martinez’s “First Sleep” (from the motion-picture soundtrack Solaris, 2002), which Nsingo says she chose because of its “gentle building,” “it hints at transformation,” and the steady driving bass, which “helps emphasize the notion of migration and moving.” As the music builds, Nsingo moves more frantically, quickly gliding throughout the opulent room, below the gods’ feast, and beside the western philosophers… As the crescendo climaxes, her frenzied footwork and movement shifts, and concludes with the ultra-slow mime of the tribal dance, until she rests motionless. For Nsingo, this dance, mymothersshoes, is about loss, about cultures/worlds colliding, and about misinterpretation between cultures. It is also a chance, she explains, “to document my family’s history, much like the frescos and sculptures in the Villa document those who have lived there previously.”

|

Fig. 1 Villa di Corliano |

|

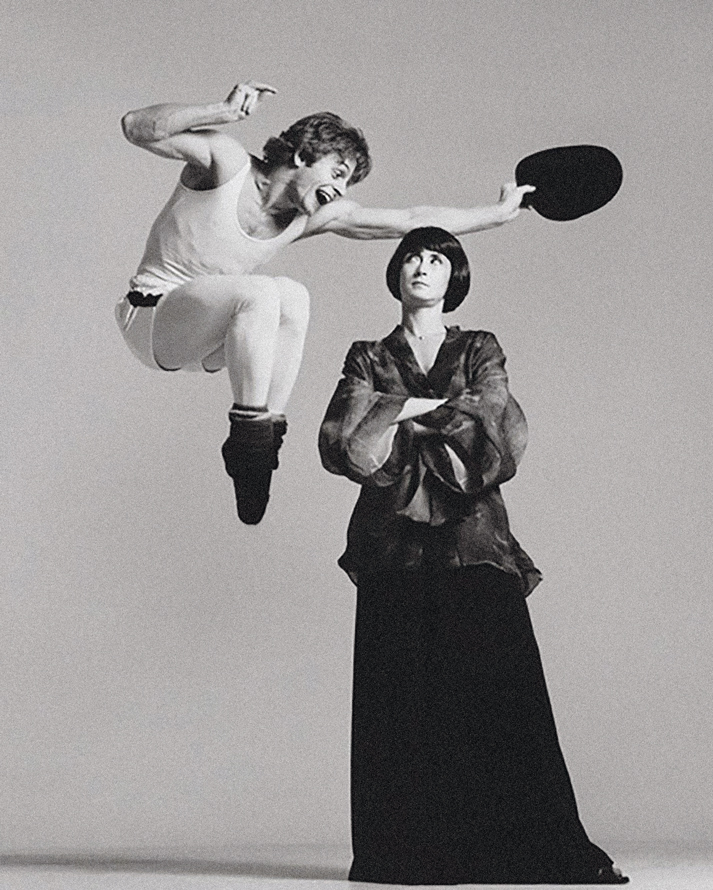

Fig. 2 Lena Liv - I traveled beneath the sky |

|

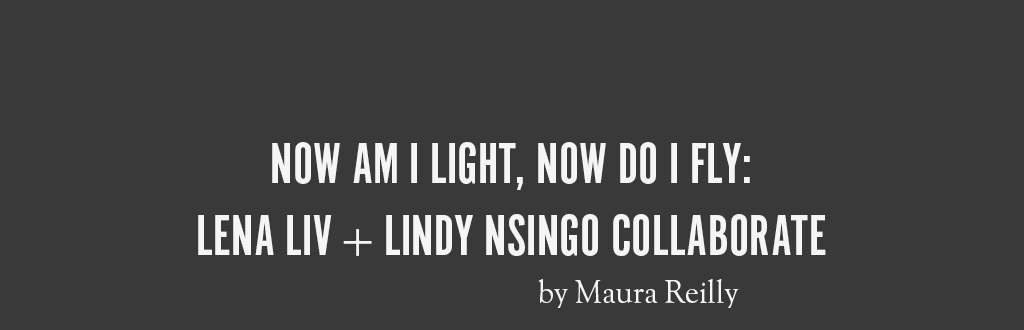

Fig. 3 Mikhail Baryshnikov & Twyla Tharp |

While there, in the villa, dancing, Liv documented Nsingo.

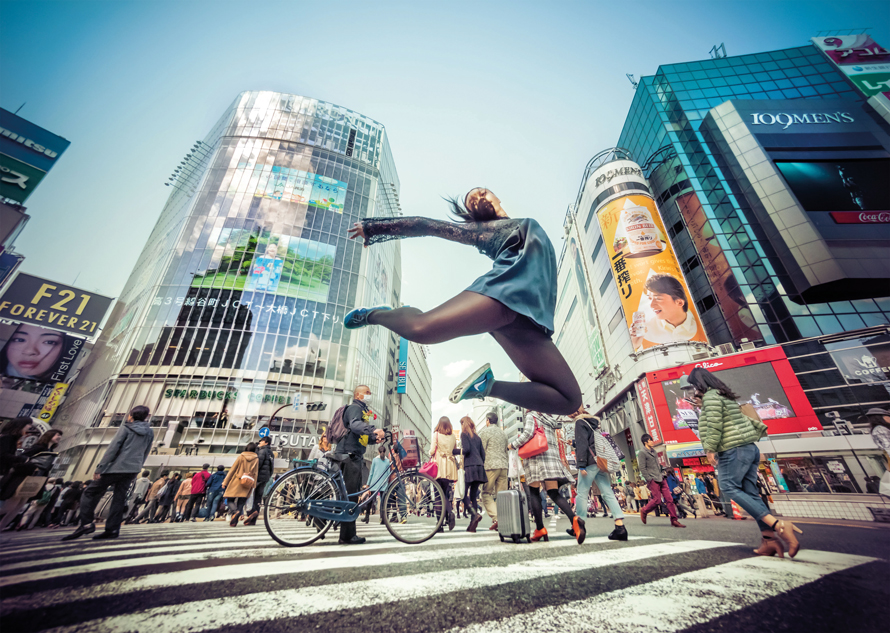

Of the resulting works, the pastel, I traveled beneath the sky (2014-15) (Fig.2) (a title taken from Arthur Rimbaud’s poem, “Ma Bohème,” 1889), is of particular importance. Composed of almost three-dozen, small-scale pastel drawings on hand-made paper, this monumental collage presents several views of Nsingo dancing, simultaneously. Each drawing is exquisitely executed in such perfect verisimilitude that one might mistake them for photographs; that is, until one sees up close the soft and unmistakable velvety texture of pastel on paper. As a sum of its parts, the large pastel coalesces before the spectator’s eyes into a single image of a dancer in perpetual movement. It does not appear as a still image of a single dance pose, as with Richard Avedon’s 1975 portrait of dancers Mikhail Baryshnikov and Twyla Tharp (Fig.3) or even Trey Ratcliff’s image of Nsingo (Fig.4), but rather as a quasi-filmic depiction of a single dancer in multiple poses.

Likewise with Golden chains from star to star ... And I dance (a title taken from Rimbaud’s “Illuminations”), which depicts an image of Nsingo in triple. Composed of three overlapping glass panes, the image merges in the viewer’s eye as a dancer suspended in three dance poses simultaneously. In sum, the image describes the visual spectacle of movement. Given the dynamic complexity of this work, as well as the pastel, one might be tempted to compare Liv’s images with the early photographs of Etienne-Jules Marey or Eadweard Muybridge, which prefigured film, and which equally suspended time by freezing movement in a single image. However, these two compositions more closely resemble Futurist images like Umberto Boccioni’s painting, Dynamism of a Soccer Player (1913) or Antonio Bragaglia’s futurist photo-dynamics (Fig.5) - both of which embodied the early 20-th century artistic movement’s search for a “universal dynamism” reflective of a rapidly changing, modern world. In their images, past and present tenses are suspended in a single image, as are multiple poses, perspectives, and angles. Bragaglia’s Changing Positions (1911)is a case in point: a gesturing man is captured in multiple positions and perspective. His concern is wholly futurist: to encapsulate in a single image the passage of time.

While Liv’s new works share the Futurist quest for dynamism, and for the suspension of past and present, she produces these effects using very different means - vis-à-vis the technique of collage or overlaid glass panes.

Further, the dramatic impact of Liv’s works depends wholly on the overlapping planes of the collage and the luminosity of the glass panes, lit from above and behind. This produces a hovering sensation, which further emphasizes the dancer’s movement, especially as one approaches the work itself from differing angles. Moreover, as Liv states emphatically, she is not a photographer. Instead, these are “3D works/ sculptures/constructions,” which, when hung on the wall, protrude twelve inches from the wall, versus a flat photograph. For Liv, photography is utilized as a means to an end, as “raw material”; and she uses Photoshop to “paint” the image and to “build light,” she says. The end product is always sculptural.

In earlier constructions, Liv used eerily faded black & white pictures from bygone eras, which she “found” at flea markets or in historical archives. She then enlarged and manipulated the images in order to isolate a certain object/subject, i.e., a boy’s face, an empty bed, a clock, which emerge from the darkness like a vision in a dream. The images were often juxtaposed with related or unrelated objects, such as old lamps, nightshirts, dolls, shoes, hobbyhorse, which produced a surreal or uncanny effect. In one, for instance, Tavolo bianco (2002-03), a black and white image of a table is accompanied by a “real” tea-cup. In another, Untitled (Boy with a Blue Ball) (1999), a solemn looking boy stares out from inside the top and bottom covers of a metal box; a blue ball (made from handmade paper) tucked into the corner, a metaphor for child’s play (Fig.6). This dramatic combination of the two-dimensional images and the three-dimensional objects produces a conceptual rift between reality and surreality, between representation and metonym.

|

Fig. 4 Lindy Nsingo by Trey Ratcliff |

|

Fig. 5 Antonio Bragaglia - Salutando |

|

Fig. 6 Lena Liv - Untitled (Bambino con pallina blu) |

Liv’s haunting images are generally en-coffined in heavy steel boxes: light counters weight, massiveness juxtaposes fragility. The constructions resemble picture-chambers echoing forth often-ghostly narratives of pain and lament. Yet, they are only referents, for there is no definitive narrative closure, but only the juxtaposition of object (blue ball, i.e.) and image (boy, i.e.) that produce a tentative connection in the viewer. Some are like pictograms or image-codes, demanding visual interpretation while being forever evasive and open-ended; others are like memento moris: meditations on death that remain imprinted on the viewer’s mind, remnants of a time long passed. As Karl Ruhrberg explains, her constructions are picture-stories, “in which time does not flow but is suspended: complex ‘snap-shots’, in which past, present and future merge in an indirect, though meditative, logically comprehensible fashion: melancholy documents of solitude and loss, silent and unsentimental”xi.

It is the earlier work’s uncanny and melancholic sensibility that aligns it conceptually and visually with the work of Christian Boltanski. However, while the latter’s images are personal, individualistic, or semi-autobiographical, Liv’s are specifically meant to address the universal. Her practice seeks to sift out the superfluous and focus, like the Pre-Socratic philosophers, on the “essential nature of things.” As Liv explains, “I try not to represent but to give the impression of something very intimate, very close to all of us and yet at the same time indecipherable. It might be an expectation or perhaps a promise, a doubt or a question. It is an attempt at sacralisation, simplicity, essentiality and truth”xii. Unlike Boltanski, then, Liv is fascinated by the idea of an archetypal, essential form, a universally comprehensible principle or formulation; that is, a form (like a fossil) that is universally understood without explanation. A labyrinth, a form she often utilizes, for instance, is a prehistoric symbol that signifies both death and rebirth. Childhood is also a universal phenomenon - and is “a synonym for the unrepeatable, the forever lost, … for the finiteness of time,”xiii and, as such, is a subject that emerges with great frequency in her work. It is a primal moment shared by all humankind, and is one not bound to her personal history; rather it is an idea a posteriori. It is this reasoning that also helps to differentiate her practice from Boltanski’s. In other words, if Boltanski had created the image Ricordo di anno scolastico 1914 (1990-91), most viewers would assume it was a reference to children who perished in the Holocaust (Fig.7). However, in Liv’s hands, it is a symbol of childhood itself, and of persons who today are no longer living. That is her picture’s eidosxiv.

Like Liv, Nsingo is also concerned with the reduction of her chosen medium, dance, to its essence: How can the most minimal of movements produce the most dramatic effects?

Posing a question like this is not out of the norm for Nsingo, who was trained at the Northern Contemporary Dance Company in Leeds (2006-9), where she was schooled in the lineage of Martha Graham, whose favorite dictum - “Dance is the hidden language of the soul” - plays out in Nsingo’s choreography. Through Graham, Nsingo learned that dance could have a political and social relevance, as well as deep meaning. (As Graham explains: “I wanted to begin not with characters or ideas, but with movements…I wanted significant movement. I did not want it to be beautiful or fluid. I wanted it to be fraught with inner meaning, with excitement and surge.”xv) Through Graham, Nsingo learned to emphasize the center of the body, and the importance of being grounded in movement.

|

Fig. 7 Lena Liv - Ricordo di anno scolastico 1914 |

|

Fig. 8 Lindy Nsingo in collaboration with Shaun Gladwell |

|

Fig. 9 Fall Apart by Lindy Nsingo |

Nsingo has also studied ballet, modern jazz, and hip-hop, and has participated in Physical Theatre, where she learned to use movement as an effective tool in theatre. However, today, she mostly looks for inspiration to choreographers like Anne Teresa De Keersmaeker, Jiri Kylian, Jasmin Vardimon, Crystal Pite, and Hofesh Shechter - most of whom emphasize the importance of narrative and repetitive gestures. In addition to her more formal training and observations of her contemporaries, Nsingo has been greatly influenced by the choreography encountered in music videos, beginning in the 1990s with songs by New Order, Peter Gabriel, Sonic Youth and Kylie Minogue. Above all, however, it was the music video for “Chase the Sun” by Planet Funk (2001) that had the most profound effect on her choreography at the time. In the video, the characters are locked in a psychiatric ward and dance quite awkwardly, with nervous ticks, and frantic movements, with no consciousness of the camera, as with other music videos. (Incidentally, the dancers featured in the video, such as Rachel Krische, Frank Bock, and Eddie Nixon, are now major players in British dance.) It was the innovative, yet slightly eccentric, everyday movements that inspired Nsingo - and it is something she has continued to employ in her practice. For instance, in 2014, Nsingo performed in a synchronised pas de deux with Australian artist and skateboard aficionado Shawn Gladwell, during which the two danced to the same songs by Nicholas Jaar and Bonobo, but at different times (Fig.8). During her dance, Nsingo displayed pliés, hip-hop gestures, slow-motion modern dance, athletic gestures - all combined seamlessly, like a complicated pastiche of dance codes. Similarly, in a recent work, Fall Apart (2015), Nsingo choreographed two dancers experiencing sleep terrors, using dance moves from multiple genres - from ballet and hip-hop to everyday gestures (Fig.9). The dance was fitful and restless, as the performers tossed & turned, jostled and cuddled, yearning to reconnect. In the end, there is indeed reconciliation; the light fades as the couple slow dances. Like the Villa Corliano piece (and the Gladwell work), Fall Apart is a postmodern amalgamation of dance symbols and styles that flicker in/out of recognizability.

This concept of dance as system of codes is explored further in two other works from the Dancing Makes Me Joyful series: No words, no thoughts: but in my soul will grow a boundless love (a quote taken from Rimbaud poem “Sensation” from 1870) and But all joy wants eternity, wants deep, wants deep eternity, both from 2015 (Figs. 10+11). In the former, a large triptych, Nsingo (wearing a pale blue dress) is represented in three dramatic poses; in the latter, Nsingo presents nine variations - a sum total of twelve dance movements between the two works. They are like Mallarmé’s hieroglyphs or pictograms, from which a spectator can recreate Nsingo’s choreography based on the twelve dance positions/codes expressed therein.

In both of these images Nsingo’s body is dwarfed by the enormity of the surrounding architectural components. Liv’s emphasis on the space surrounding the dancing body harks back to any early series of works, Moscow Metros (2006-9), large-scale images on glass depicting the Russian city’s magnificently decorated subway interiors built during the Stalin-era as “palaces for the Proletariat,” with themes based on medieval architecture, Soviet Art Deco, the home front struggle of the Great Patriotic War, WWII, among others (Fig 12). Liv documented the subway images in the early morning, before passengers crowded the stations, and represented only a few, refugee-like figures wrapped in layers against the cold. The juxtaposition of the old subway architecture and the melancholic figures of today functioned to collapse the past with the present in much the same way that Nsingo’s dance is suspended in time and space.

The scale of these new image-constructions is monumental - as is often the case with Liv’s sculptural works, which are generally enormously heavy and large in scale. In But all joy wants eternity, wants deep, wants deep eternity (a quote taken from Nietzsche’s book Thus Spoke Zarathustra), the image representing Nsingo performing nine dance movements is broken up into 110 small panes of glass, strung together, and lit from above and behind. The effect is of a large stained glass window, as one might encounter in a cathedral. It should come as no surprise, then, that during her formal training at the prestigious Stieglitz St. Petersburg State Academy of Art and Industry, Liv studied multiple glass techniques (blowing, stained glass, etching) along with more traditional studies like painting and drawing.

|

Fig. 10 Lena Liv - No words, no thoughts; but in my soul will grow aboundless love. |

|

Fig. 11 Lena Liv - But all joy wants eternity, wants deep, wants deep eternity. |

|

Fig. 12 Lena Liv - Maiakovskaja (From the series Cathedrals for the masses / Moscow Metro) |

|

Fig. 13 Lena Liv - Donna con sigaro |

|

Fig. 14 Gipsoteca, Possagno, Italy. |

Glass is an important medium to Liv, who underscores light as being as important a concept to her as line and color. Since her aim is often to create an image with light, the glass helps to emphasize that lightness. By imprinting her images on glass, Liv is able to isolate what she calls “the essence of the image,” emphasizing certain content using light, and deemphasizing other content by relegating it to shadow. For her, it is the “essence” (that which is in light) that is eternal. For instance, in an emulsion on glass work titled Donna con sigaro, 2002-2005, a heavy-set, masculine woman smoking a cigar and holding a doll, emerges from the darkness (Fig.13) Unlike these earlier works, however, in this recent body of work, as with the Moscow Metro series, Liv is utilizing not just black and white, but full color imagery. The result is astonishing and appears to mark a turning point in her work. While the earlier images functioned at times like memento mori, it could be argued that the newer works exemplify a radically different dictum, momento vivere. These are not dark images of persons or things from the past, but rather colorful images of ‘live’ subjects, in this case Nsingo. Moreover, while the earlier images are of immovable/still subjects from the past, these are of a contemporary subject from the present, a body in flight, mid-movement.

In 2016 Liv and Nsingo will be collaborating again. On this occasion the duo will meet at the Museo Canova in Possagno, Italy, amongst the stunningly beautiful neoclassical sculptures produced by Antonio Canova (1757–1822), which are installed within the artist’s home, as well as in the nearby Gipsoteca, built in 1836 (Fig.14). In this historic setting, Nsingo will perform a newly choreographed piece, while Liv will document in preparation for what will inevitably be large photo-constructions on glass. As we anticipate this new performance, and to paraphrase Mallarmé, “What about those pointings, tappings, lunges, and bounds” - “What will they signify?’ What will Nsingo’s dance codes and signs relay in that particular setting? We will wait, impatiently.

Bibliography

i F. Nietzsche, Così parlo Zarathustra, parte I, Del leggere e scrivere, trad. it. a cura di G. Colli e M. Montinari, Adelphi, Milano, 1985, p. 41.

ii A. Rimbaud, Illuminazioni, trad. it. a cura di A. Marchetti, Pazzini, Verucchio, 2006, p. 57.

iii S. Mallarmé, Filosofia della danza,. Altro studio di danza, i fondali del balletto, trad. it. a cura di B. Elia, Il melangolo, Recco, 2004, p. 62.

iv Ibid.

v M. L. Shaw, “Ephemeral Signs: Apprehending the Idea through Poetry and Dance,” Dance Research Journal, Vol. 20, No. 1, Summer 1988, p. 3.

vi S. Mallarmé, Filosofia della danza. Altro studio di danza, i fondali del balletto, cit., p. 60.

vii M. L. Shaw, “Ephemeral Signs: Apprehending the Idea through Poetry and Dance,” cit. p. 3.

viii Ibid.

ix A. Panajia, Villa di Corliano: Il più bel Palazzo che sia intorno a Pisa, Felici Editore, 2008.

x Intervista con la ballerina.

xi Karl Ruhrberg, “The Evocation of the Shades: Note on Lena Liv’s Environments and Constructions in Succession,” Lena Liv, Centro Sperimentale di Arte Contemporanea, Firenze, 1990.

xii “Lena Liv, the Mysticism of Objects”: www.culturaitalia.it/opencms/it/contenuti/eventi/event_1499.html?language=it

xiii S. Wedewer, “About the works of Lena Liv,” Lena Liv: Memoria e Oblio, Galerie Reckermann, Heidi Reckermann Photographie, a cura del Centro Sperimentale di Arte Contemporanea di Firenze, Koln, 1992.

xiv Liv’s images hark back to an earlier period, and “rely for their power on a more generalized sense of the loss of childhood as a metaphor for other forms of loss...” from Stephen C. Feinstein, ed., Absence/Presence: Essays and Reflections on the Artistic Memory of the Holocaust, Syracuse University Press, 2005, p. 66.

xv www.pbs.org/wnet/americanmasters/episodes/martha-graham/about-the-dancer/497

1999.-Cast-iron,-hand-made-paper,-image,-pigment.-34-x-20-x-28cm-.jpg)